In 1619, Daniel Sennert crouched over a low furnace in his cloistered laboratory at the University of Wittenberg. The air was still and stifling. Though the room was packed, no one said a word. Instead, the several dozen learned men who had crammed themselves into the small space stared at a little white crucible as Sennert removed it from the flames. He tipped out the contents and a delicate stream of molten silver ran from the crucible to collect in an earthenware bowl.

Gasps filled the air. Such a thing wasn't supposed to be possible. Chills ran down the spine of every man in that room, even Sennert himself. For he knew, in that moment, the world had changed forever.1

The State of Sennert's Science

Photo credit: Google Books

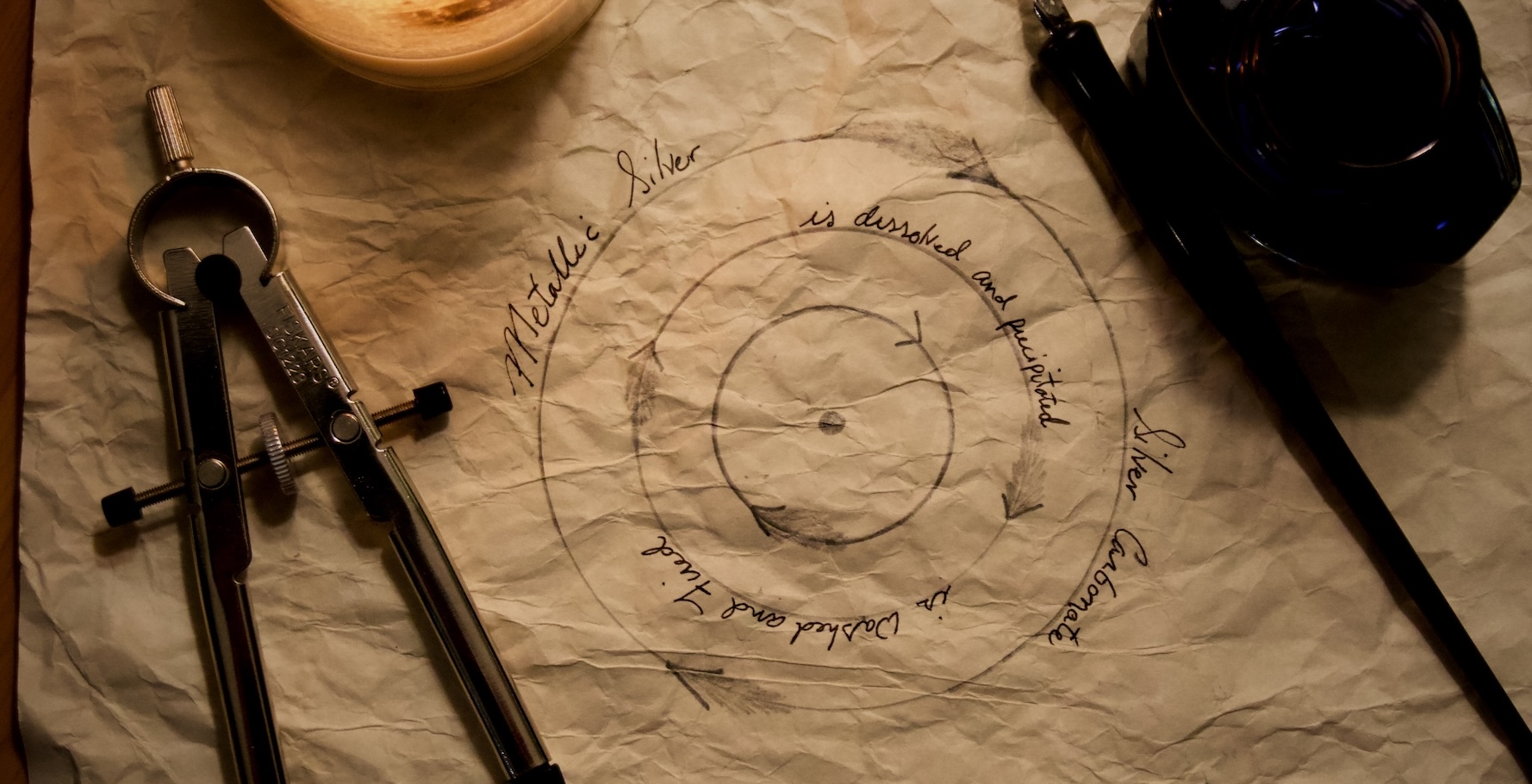

Photo credit: Google Books

In the days before Newton, Boyle, Kepler, and others remade the process of scientific inquiry, humanity's understanding of nature and our scientific methods were markedly different. The writings of Aristotle formed the foundations of natural knowledge and the workings of matter were explained by the qualities imparted by abstract Forms, rather than the formulation and arrangement of physical atoms.

From our vantage now, it might seem strange, but the Aristotelean scholars of the time were quite comfortable with their theory's ability to explain the natural world. While their understanding of nature was changing over time (as does ours), it had stood for centuries and they had little empirical evidence that anything was terribly awry.

That is, until the discovery of the mineral acids.

Nitric, hydrochloric, and sulfuric acid were discovered gradually during the middle ages with the first (known as aqua fortis) discovered around 1300 C.E.

Before the use and widespread adoption of the mineral acids in scientific inquiry, it was understood that all materials underwent the same general process: what Aristotle called Corruption and Generation.

Broadly speaking, nature itself generated all primary materials from the four Aristotelean Elements (sometimes five) and then either Nature (or God) imparted that matter with Forms, which determined the perceivable qualities of the matter. Trees were generated (grew) from the earth, then died or were cut down in the process of corruption that resulted in wood, corrupted further to rot and earth, or ash and smoke (depending on the method). The specifics aren't important here. What is important is that Scholastics understood this to be a one-way process. Nature could (re)generate matter from the elements, but after that it was all downhill. Matter underwent corruption after corruption until finally resulting in the four base elements where nature could begin her (re)generation process anew. Nothing humans could do would change that.

As Aristotle said, water, once added to wine, cannot be removed again without destroying the wine.1

Then, Everything Changed

The mineral acids had been used for centuries in various places, but rarely entered the domain of philosophical debate because of a distinctly medieval distain for "practicals" in the development of physical theory. This isn't so much a distaste for experimentation, as is often claimed, but a dislike of certain professions (like that of the tanners or chymists) who followed recipes instead of pursuing a connection to more philosophical ideas. Chymists, for example, were not thought of as practicing rigorous academic study. Their work wasn't connected to any pedigreed Aristotelean foundation, and so they were mere "empirics". Their study was without academic merit.

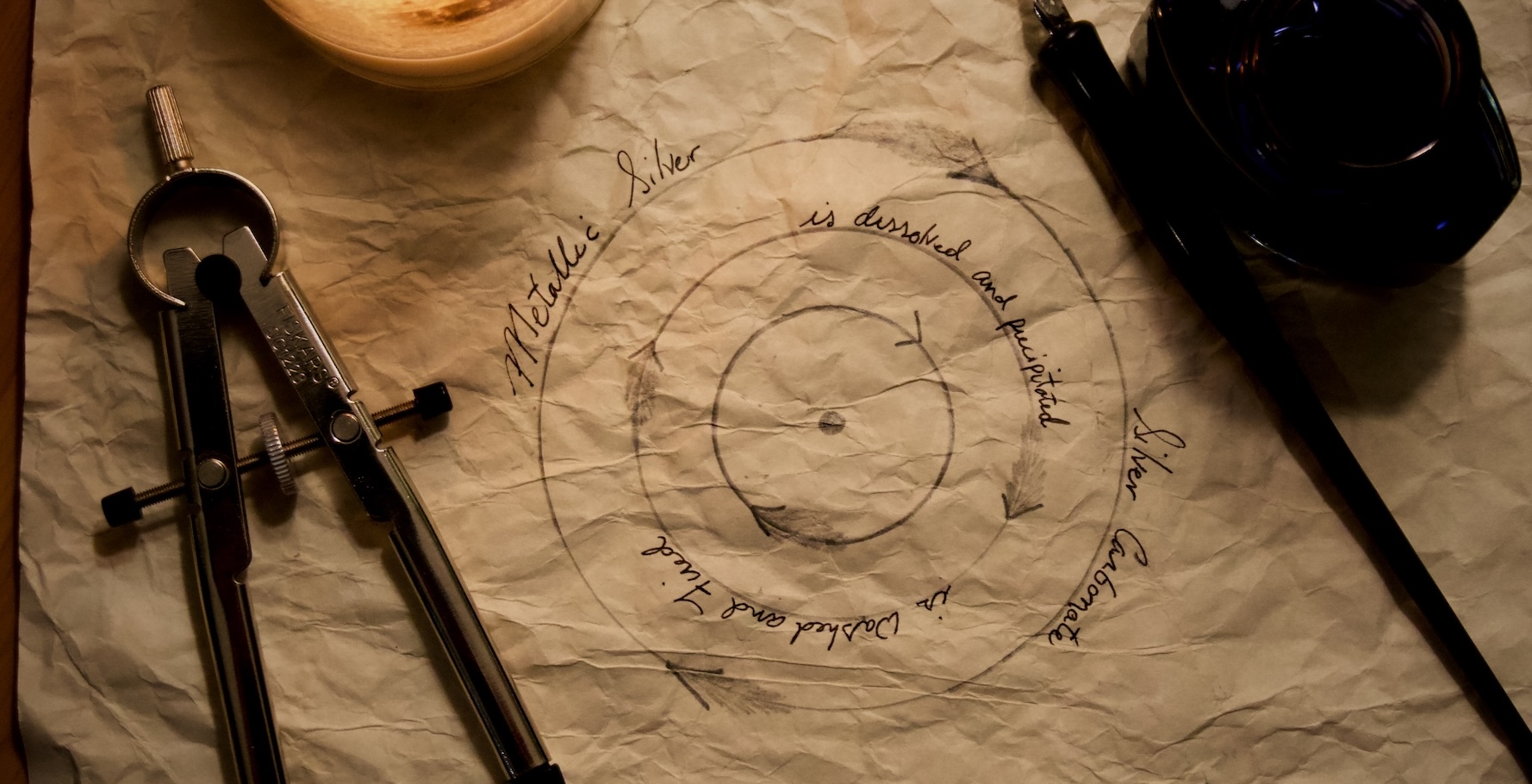

However in 1619, Daniel Sennert, a professor of medicine and an unusually practiced chymist, discovered a curious phenomenon. Sennert was investigating whether dissolving silver in aqua fortis resulted in a truly homogenous mixture (what Scholastics called a mixt). A true mixt would mean that the silver was irrecoverable because a genuine corruption had taken place.

When Sennert pours his liquid through a fine filter paper, he sees no particulates of silver— evidence of a true mixt.

He then adds salt of tartar (potassium carbonate) to his mixture and a white precipitate emerges. He filters and washes this new material and then puts it in a crucible and heats it. Eventually, what emerges is pure, molten silver. Sennert has performed a genuine corruption and then retrieved his starting materials, something which should not have been possible.

Sennert's experiment was notable for two reasons. First, the development of "corpuscular" or what we could call "atomic" theory is notable because it was considered to go against the commonly understood teachings of Aristotle and second because, as William Newman wrote:

In doing [this experiment], [Sennert] had simultaneously shown the inadequacy

of the current scholastic theories of mixture while also providing a convincing demonstration of the reality of semipermanent atoms that experience no substantial modification.2

While Sennert himself was able to shoehorn enough traditional theory into the Scholastic framework to explain his results, this same experiment would later be used by Robert Boyle in his book The Skeptical Chymist to attack the foundations of Aristotelean matter theory and help to begin the reformation of chemical science into what we know today.

Chemical Telescopes Today

The story of Daniel Sennert is the story of science. Ages had come and gone where Aristotle's theory (with numerous additions and changes) had come to dominate Europe’s intellectual understanding of the world. The theory explained much about the world and several tweaks, additions, and modifications existed to fill the gaps where the base theory fell short.

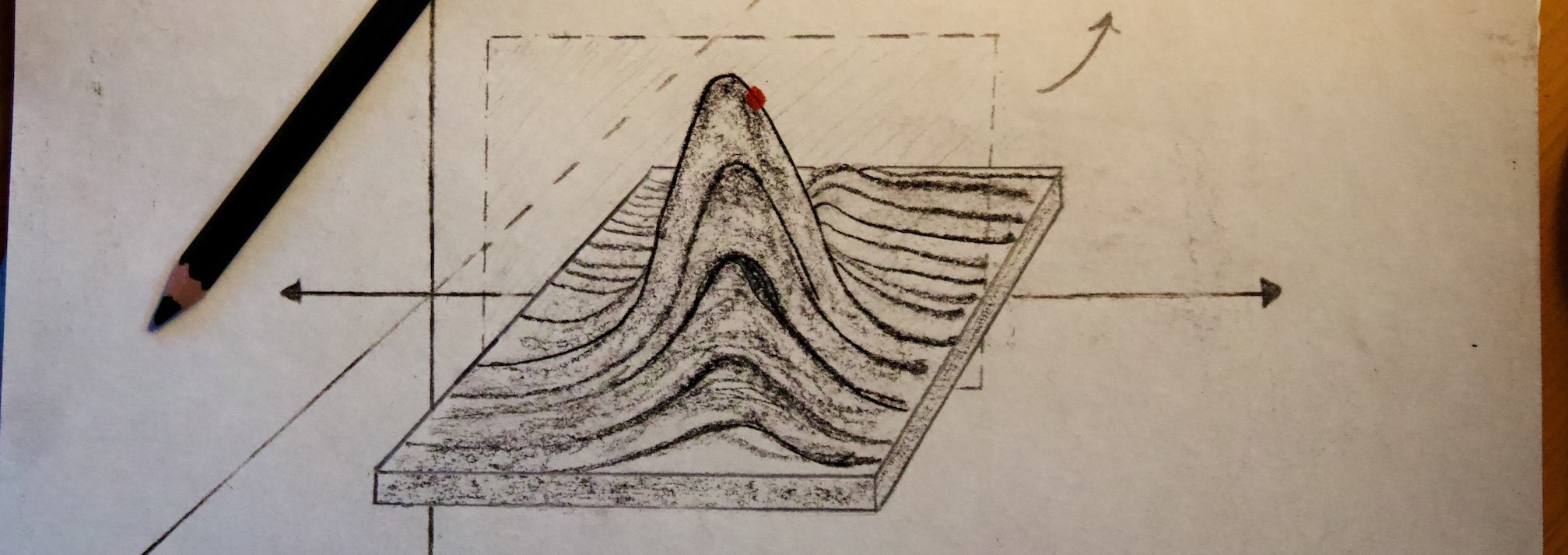

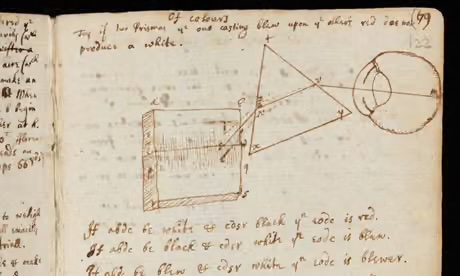

It wasn't until a new technology came along, a new method of looking at the world and investigating its workings, that the old theories began to crumble. Like Galileo and his astronomical telescope, the mineral acids were a chemical telescope that allowed European scholars to probe nature in new ways and find new evidence that didn't fit their prior understanding. Then they had to come up with new theories to explain it all.

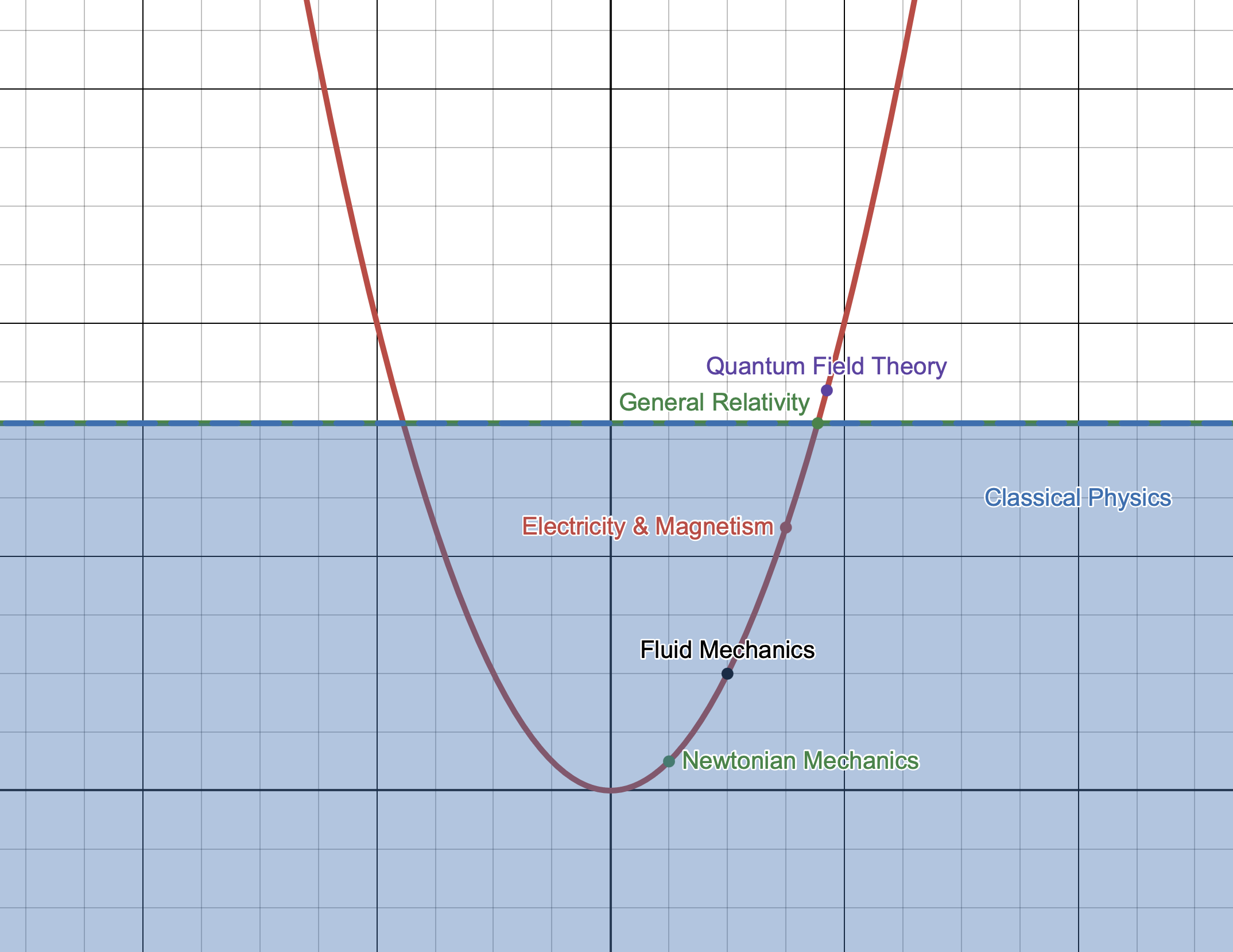

Today we may be in a somewhat analogous place, albeit with far better theories. We can explain nearly every classical physical phenomenon we encounter and we have supremely accurate theories for the behavior of even the most minute particles in all the universe. However there are still many gaps, places where our theories break down or contradict each other and can therefore have no explanatory power.

We've tried to solve this problem with additional theory development, however so long as contradictory experimental evidence is scant we will find ourselves akin to the scholastics of Sennert's time: philosophizing and debating increasingly complex theories that can be tuned any number of ways. The unobservable dimensions, fields, or forces of today are more akin to the abstract Forms of Scholastic thought than we may like to admit.

The Pendulum Swings

To paraphrase Dr. Asaf Karagila, science is primarily a social activity done by scientists.4 And that social activity has, for lack of a better term, fads. In the long course of science, there have been numerous swings back and forth between a focus on experimentalism and theory development. Theory development has seemingly always held the more prestigious position in the sciences, but it's experimentation that truly drives progress.

It was the failure of the Michelson–Morley experiment that inspired Lorentz and Einstein to remake relativity. It was the failure of classical theory to explain black-body spectra that inspired Max Plank to discover the foundations of quantum theory. And it was the failure of Aristotle's Generation and Corruption to explain Sennert's recovery of silver that helped Sennert and later Boyle and Lavoisier to reform chymistry into modern Chemistry. In each of these cases it was the discovery of contradictory, not complementary, evidence that spurred the greatest periods of theory development.

From all of this—astronomical or chemical telescopes alike—it seems that the wise words of History tell us that when our science gets stuck, it's best to look away from the blackboard and instead ask the Universe some hard questions.