It took me by surprise to learn that this post was now a decade old:

Last week I decided to leave Spotify. I've been using the service for almost 2 years now, and overall I've really liked it... It's hard to explain why [I'm leaving], but I guess I feel apprehensive about Spotify being in control of how and where I listen to music in ways I haven't been before.

I remember the inciting incident so viscerally. I wanted to AirPlay a song to my TV, but that device wasn't "approved by Spotify". It's an MP3 and I couldn't jam out to it because of the policies of some company. I was so angry, so I left. Without a viable alternative, I started buying albums in the iTunes Store like it was 2007 all over again.

It's been ten years now, and I do not regret that choice for a minute.

Buying Music in 2025

There is a distinct freedom that comes with owning your own music library. The knowledge that your music isn't going to go away on you someday when you stop paying for access is nice, but even better is the feeling that you're free from the capricious whims of any corporate policy change. If Apple, or whomever, decides to be a jerk, you can take your ball and go home. Your library is yours and can be ported easily to any other app or service you want.

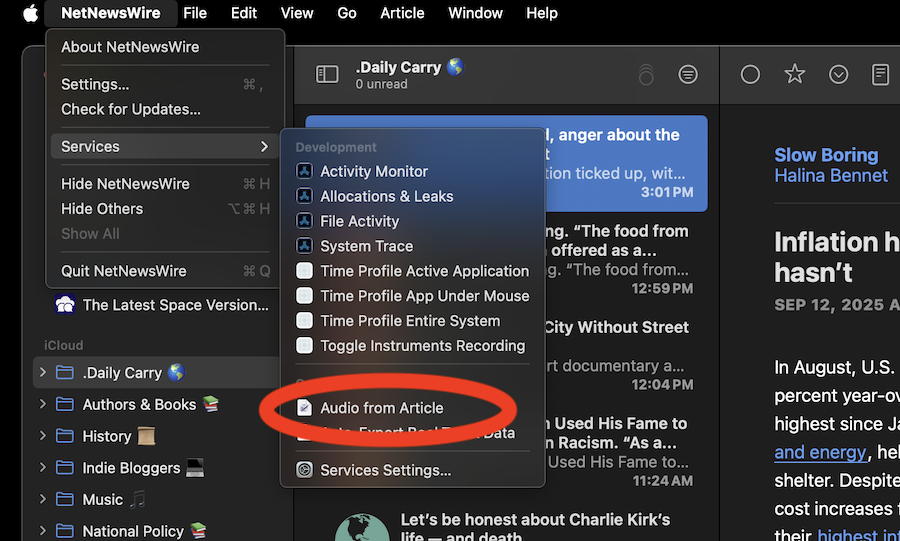

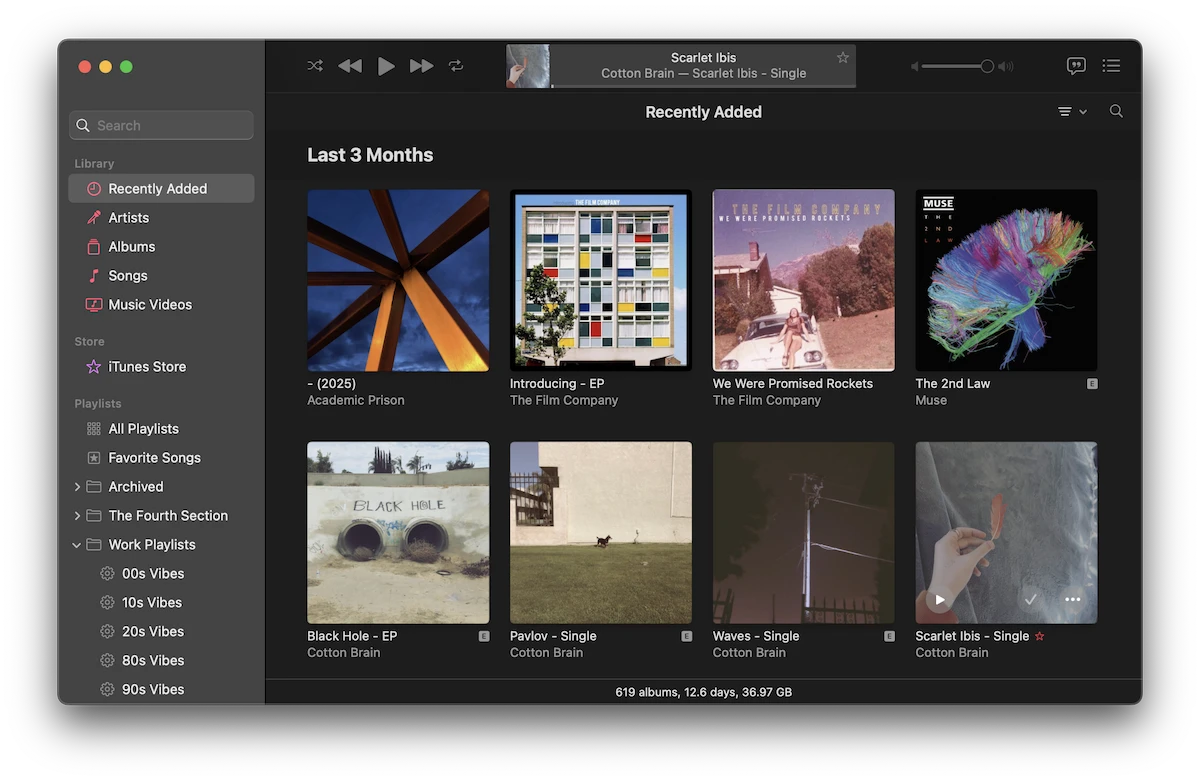

Of course there's the rather sizable downside to all of this, which is that music today is largely dominated by platforms like Spotify, etc.. When you buy music in 2025, you're going against the grain. Apple Music has seemingly forgot that people have personal libraries and links exclusively to Apple Music when it is searching for tracks and the iTunes Store is getting quite long in the teeth. Recently, albums have started appearing twice in my library at purchase-time and that mess has to be manually cleaned up.

Still, iTunes Match continues on and so my laptop and my phone continue to be in sync for only $24/yr. If this ever went away, I could always sync manually—but in reality I'd probably just switch to using Plex for music.

Buying your music is certainly a dying art in 2025, but for now at least, the apps and stores still exist and, largely, work just fine.

Oh, and nobody tell Apple that iTunes Match hasn't been adjusted for inflation, like ever.

Unspoken Advantages (and a few Disadvantages)

When I started curating my music again in 2015, I had a few random singles (from those old Starbucks song cards) and a few random anime soundtrack albums I'd gotten from somewhere, back in the day. But, since my musical tastes had changed drastically, I was basically starting from scratch. For the same price as Spotify, I was able to get one album per month until I built up a sizable library—then my investment started to pay off. I'd go months without buying an album, and I had the freedom to play them anywhere. It was glorious.

It was around 2017 that I started getting into listening to albums as standalone works, rather than listening to custom playlists of singles. From there it was a straight shot into the world of collecting vinyl records, a hobby I've really grown to love. Buying and listening to whole albums also really put me in tune with the entire feeling of a band. Sure, not all of the songs on an album are bangers, but as Colin Meloy of the Decemberists put it:

[For me, an] album was not just an analog to a short story collection, it was sometimes a novel — each song a different chapter, a different panel in the quilt.

I took artists at their word; the order of an album was as intentional as the lyrics inside the songs. A thread was there to follow; clues to unlock. Even if there was no literal connection between the songs, there was a pattern and a rhythm to the thing.

It's one, long song. That realization changed how I conceive of recorded music.

The main advantages, beyond the freedom I've already mentioned are primarily for people who are really into music and the music ecosystem. Buying music continues to be the best way for artists to make money off of their art. Artists continue to receive 70% of an album's sale price on iTunes compared with the $0.005/stream rate that Spotify charges. As well, maintaining your own music library is the easiest way (even today) to follow indie or local bands who may not have fronted the costs to put themselves on the big platforms.

Buy music on Bandcamp or download it from Soundcloud, stick it in the Music app, and you're off! No switching between a hundred apps, no platform lock in. Just music. It also helps immensely when you're recording your own music (as I do, frequently for my band).

That said, there are some distinct disadvantages to buying music. You miss out on the recommendation features and smart playlists (Genius does still exist but it does and has always sucked). Also, it's basically impossible to share playlists with others or import them for your own use.

You can still burn a CD though, if that's your thing.

Some Other Musical Thoughts

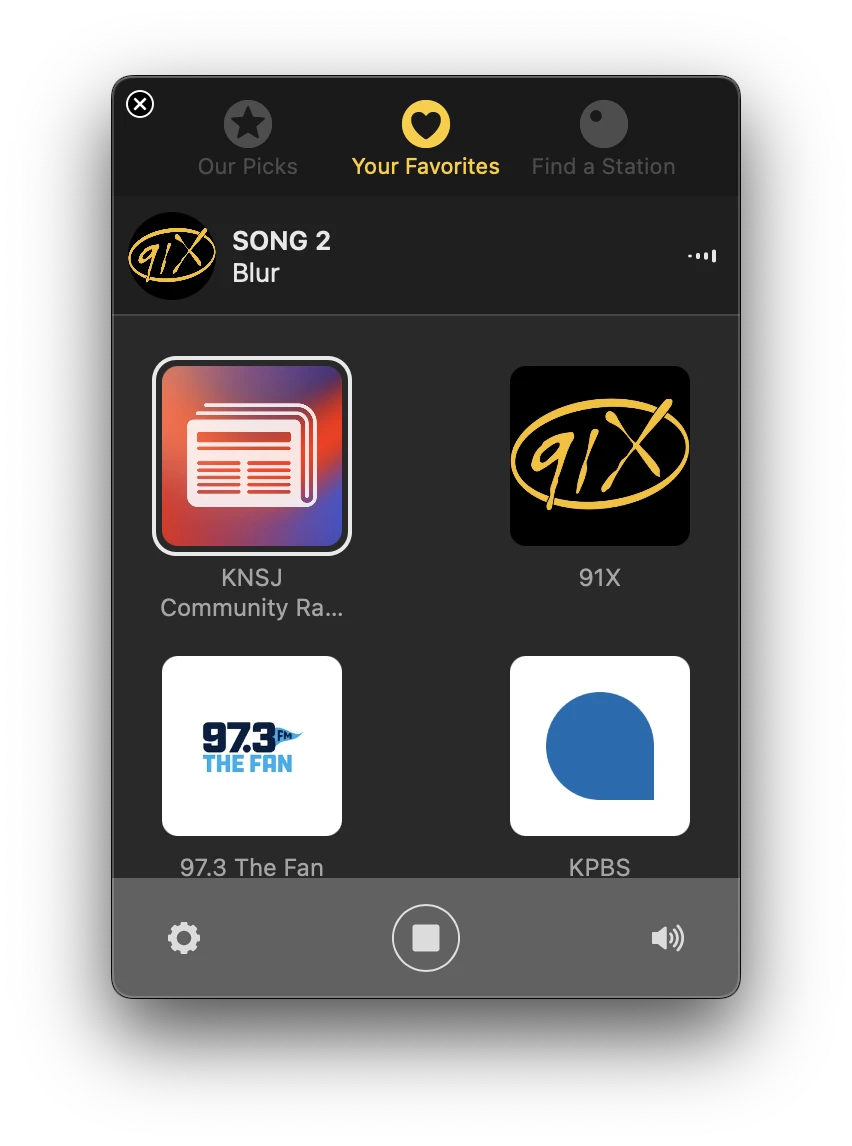

Recently I've gotten back into listening to internet radio. I go in an out with this particular interest, but one thing that's made this particular venture back into the depths much more enjoyable is the app Triode by Iconfactory. Music.app retains its predecessor iTunes' ability to stream internet radio (as well as burn the aforementioned CDs) but the integration was always half-assed. Triode is just so much better.

Even now, in 2025, I can't see myself switching away from this world any time soon. Buying music is a pain and it's a fading feature, but it's still the best way to actually own and control the music you listen to, and it's the best way to support the artists you love.

Like so many technologies of the early web that we've now nearly lost or forgotten, it's flaws are real. Like RSS and Podcasting, it takes a long time to curate and gather the blogs, shows, and music you want to enjoy and there's a lot of dependence on informal recommendation networks like those from friends or word-of-mouth via the messy world of meatspace (remember that term?). It's a very human, not algorithmic world, and I love it.